1. LE CHÂTEAU: THE KINGDOM OF THE VARIOUS ARTISTS

Elke Van Campenhout

“In a historically advanced period there is no one ideology,

but only ideologies – in the same way as there is not just Art, but the various arts, or

as there are several relevant artistic trends to be distinguished, corresponding with

the various influential social strata”. (Arnold Hauser)

1) VA and Various Practices

After the unfortunate death of the Late Trudo Engels in 2009, Various Artists took over, erasing his name as a solo artist and working further on the myriad paths, ideas and disciplines that Engels had developed over the years. Browsing through the CVs it becomes clear that the VA is a rather quirky muddle of characters. Comprising visual artists as well as performers, an architect, a former academic as well as a cat-killing eco-activist and a self-taught sniper, Various Artists seems to cover quite a wide range of artistic trades.

In a sense the various-ness of the VA is somewhat of a mirror of the contemporary arts scene, reflecting the oppositional qualities of approaches that are performed within the group. Most of the VA’s practices seem to be strongly embedded in the currency of the everyday, of a state of affairs that envelops most of our lives but that in its utter quixotic ephemerality often escapes our attention. However different their approaches, techniques and strategies might be, the work stumbles in its attempt to get a grip on a globalized world of signs and economies gone haywire. Central to the projects is a sensitivity to the languages of corporate aesthetics, advertising and technology: the VA formulate their practices out of the need to distance themselves from an all-encompassing language of seduction, statistics and seemingly transparent communication through the use of repetition, blurring and poetry. In the kingdom of VA the artist relates (in)directly to what surrounds him, a bricolage of hidden networks of meaning, of murky acquaintances between the arts, science, economy, technology and poetics of the ordinary…

However popular the collaborative practices might have become in recent years, the VA cannot be considered a collective in the usual sense of the word. Not only because they originally sprung from the head of a single artist, but also because their ideological frameworks stand widely apart. Their incongruently common name does not seem to cover a common goal, but rather the lack of that, replacing the goal by a shared attitude of taking a (non)position in the art market. Visibility in this case is not considered the height of desirability. Nor is the development of a successful strategy to gain access to the art market a driving force for the group. They share an attitude, in other words, that keeps them hidden from the aesthetic and economic exchange politics of the contemporary arts discourse that rules the relations between artists, sellers and buyers. The VA resent the possibility of transparency: it is not exactly clear how many artists are part of the group, for example. On top of that, some of them get temporarily parked, like Aude Thensiau, who was admitted to a mental hospital somewhere in the middle of 2011 and has not left the premises since. In that sense, the VA group is at once fairly hermetic but semi-permeable as well. In the last years the group started to develop the ‘Being …’ workshops, which open up the practices of the different artists to a wider group of workers, allowing them afterwards to pick up the practice on the condition that they produce the work under the name of the relevant Various Artist.

(It is important to note that the payment for these works goes to the producers of the works).

2) Le Château

No coincidence, then, that the VA would have chosen Kafka as their inspiration for the development of their first group exhibition Le Château in the Luisa Strina gallery in Sao Paulo. For a show that is putting into question the different ways the current food production system directs our lives, tastes and energies, the project reflects in the first place on Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist” (the artist that in all visibility hungers himself to death for the appreciation and recognition of his public). But there is also a clear reference to Kafka’s The Castle: the nightmarish networked (un)reality of incomprehensible relations that seems to be driving the whole of society. Perhaps the scariest part of The Castle is its suggestion that everybody else seems to know how things are knotted together, but the protagonist is just shipped from one guess to another hypothesis until he comes to a sombre and exceptionally gloomy ending. It is that kind of impotence that fuels the paranoia of the work of VA Valereson da Silva, who turned this all-surrounding violence back against the viewer by developing a practice of spying and artillery. For him the violence that surrounds us is hidden in even the most simple of objects: lemons become grenades, a cookie hides a razor. His dream being to one day, when selected for the Venice Biennale, construct an automatic sniper to shoot the pigeons out of the sky above San Marco. Or the ‘conspiracy artists’ like Martaque and Marcella.B, who – each in their very different ways – lay bare patterns in the structuring of our everyday lives, which might reveal a hidden meaning. A palimpsest of a secret laid bare in all its contradictions by VA Ana Omandichanie in her erasure practices: documenting by taking away, leaving only faint traces of what lies underneath. Only for the attentive eye to see.

Obscurity becomes a statement in these gestures: the chimera of the paranoiac, the wanderings of the endless walker (Freddy Grant), the transformation of the artist starving himself in the gallery (concept by Morice de Lisle, picked up by VA), the endless repetitions of the seemingly obvious of Liam Drib or the reconstructions of pixellated images (Christl Coppens), they all introduce an intensification of the ways we experience our environments, reflecting on possible (re)constructions, pointing in different directions to what might cause our own perception (not) to pick up on the work’s invitation.

The VA seem to offer a negative mirror image to the arts scene. Much like Willy Depoortere does with his pinhole camera works, they turn the real world into its negative to come out as ‘normal’ after development. Only this state of normality, of all coming together in an established gallery, is no more than a dash of varnish. The VA momentary light up out of the dark – a guerrilla incursion into the belly of the arts – only to run back to the very individual trenches of their often extremely personal mythologies. Each of these artists comes with a biography, with scars and tattoos that largely mark their territories and strategies of work.

The range covers the romantic, often quite baroque aesthetics of the drug-induced practices of Aude Thensiau and the slightly more serene works of beach comber Cindy Janssens as well as the formal, almost modernist works of Christl Coppens and Liam Drib and the extreme, violent-induced projects of activist Bernard Leroy and Valereson da Silva. Each artist opens up one possible perspective on the position of the artist, the citizen, the simple human being, in a world that has become so tangled up in its own networking that there is only one way out of the suffocation: to hide, to analyze, or to act. Not without inner contradictions: eco-activist Bernard Leroy has made a practice of killing cats to protect the bird population in urban environments. Morice Deslisle has brought his practice to a stage of near invisibility by subtly unscrewing one screw at the time everywhere he passes. Sniper Valereson da Silva quotes the Gospel, uncovering inconsequences in the narrative.

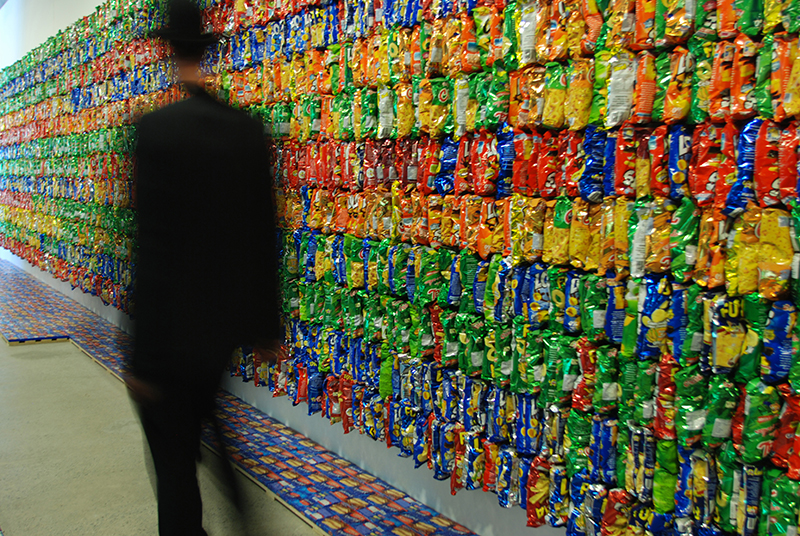

But however contemporary these artistic practices might be, they are strongly entangled in a history of performance and visual artists. In Le Château this influence is clearly felt in the aesthetics produced by Liam Drib and Christl Coppens in their overpowering food installation. Produced out of bulks of cheap, low-quality pre-packaged foods, the gallery space is transformed into a large, out-of-control living space. A Hansel and Gretel house of wonders, as seductive as it is monstrous. Cookie boxes, tins and bags of sweets piled up in rhythmic, repetitive arrangements, forming pictures, lampshades, sofas and chairs as well as several beds, these foods present themselves as what they truly are. Turning the attention of the viewer from their content (the food which, in such quantities, can no longer be imagined to be edible) to their glaring multi-coloured outsides; they show themselves as empty containers. Empty of meaning, nutritional value, substance. Or, as Clement Greenberg puts it: “To render substance entirely optical, and form, whether pictorial, sculptural, or architectural, as an integral part of ambient space - this brings anti-illusionism full circle. Instead of the illusion of things, we are now offered the illusion of modalities: namely, that matter is incorporeal, weightless, and exists only optically like a mirage”. (from the essay “Anthony Caro”, Arts Yearbook X, 1965)

In clear reference to modernist artists like Georges Van Tongerloo (Belgian artist, 1886-1965), and to a lesser degree Theo Van Doesburg (The Netherlands, 1883-1931), the artists have reduced the food items to pure materiality: dabs and lines of colour, elements in a larger scheme of repetitive relations (Drab), and fragmented perception (Coppens).

“Je travaille en vérité et pour la vérité”, Van Tongerloo is supposed to have said, but his truth was born at a time when arts production and politics were, each in their own way, still closely intertwined. Although the work was developed within the well-framed autonomous restraints of the modernist ideology, the belief system’s ambition reached far beyond the frontiers of the ‘purely artistic’. Built on the principles of simple raster-like composition, his works overcame the seemingly random in their intuitive suggestion of mathematical precision and logic, and introduced a whole new way of considering aesthetics, the function of art, and its relation to the spectator.

In Le Château a very similar strategy is being put forward. Only now, this self-sufficient claim of the modernist artwork is being fiercely challenged. Although the bold colours and patterned compositions of the objects do remind us of sculptural modernist constructions, the misleading comfortable everydayness of the objects cluttering the space, is not. As we know from the seminal essay by Michael Fried, modernist art was at war with anything that suggested the need of the artwork for an observer to give it meaning. The artwork that was perceptible in its wholeness ‘in one glance’, in all its ‘presentness’ as what it is, was, and always would be, strictly divided the artwork from everyday life. Since then a lot has happened, but seeing a seemingly late-modernist (meant here in the most literal sense) installation that brings in a clearly environmental feel renders the installation unseemly, especially since it is executed with such precision. It is at the same time a purely formal gesture, and an antithetical relational environment. It is a presence that demands to be reckoned with. To quote Michael Fried: “Something is said to have presence when it demands that the beholder take it into account, that he take it seriously – and when the fulfilment of that demand consists simply in being aware of it and, so to speak, in acting accordingly. (...) Here again the experience of being distanced by the work in question seems crucial: the beholder knows himself to stand in an indeterminate, open-ended – and unexacting – relation as subject to the impassive object on the wall or floor.” Off course Fried meant this as a sneer, but in the experience of Le Château this tension, this demand for taking a position, this false promise of comfort and homeliness that is nowhere to be fulfilled since the packages cannot be opened, the chairs cannot be sat in and the bed will stay untouched, is exactly what renders the work eerie and inhospitable. The emptiness of the materiality that is glaring out to you from the screaming colourful packaging, the sheer overload and repetitive waves of advertised promise, the house, the bed, the living space constructed out of pure hollow branding, is not self-referential. It is pointing outwards in all directions, surfing on the many tracks of the invisible networks that keep our lives together. The comfort, the fulfilment, the lie exemplified by the one VA that took up VA Deslisle’s task: ‘Endure a 34-day fast, a restrictive performance providing guidance, causing hindrance, altering or limiting the work of 8 other VAs setting up an installation with pre-packaged foods’, spread out in a bed in the middle of the gallery space.

Taking into account this action, and the set-up of the exhibition as referring to Kafka’s “The Hunger Artist”, the modernist’s ideology seems to be reversed. Modernism was art’s answer to the specialization that was the crux of a new upcoming economy. With the introduction of ever-new technologies, the world began to spin faster and faster around its own axis, a movement that was enthusiastically embraced by some of the most avant-garde arts movements. This speeding up, this demand for clearly divided fields of expertise, knowledge and efficacy, was echoed in modernism’s demand for a separate, secluded space to produce, exhibit and sell works. A transparency that was sustained by a strong male visibility culture fetishizing the (recognizable) art object, turning it from a material into a virtual object of economic and otherwise libidinal desires.

The work of VA, although at first Le Château seems to suggest otherwise in its sumptuous, overwhelming welcome, could be read as a kind of reverse modernism. The starving artist VA slowing down time, entering into the vulnerability of losing control over his own artwork. The material used refusing its own mystery, embracing its sheer virtual promise as a keepsake, a consolation prize for what it certainly never can make come true. Liam Drib’s and Christl Coppens’ contributions slide comfortably on the waves of smart design and advertising aesthetics. Fashionable and smooth as a designer’s Las Vegas, and in crude contrast to the familial setting. What they seem to suggest is that there is no insight, no inside of art, there is only the outside and the outside is out there: out of the gallery, out of the arts, out there in the places where these shiny objects are produced, packaged, distributed. Out there in the supermarkets where most of the gallery visitors probably wouldn’t enter, because bad food is produced for poor people. Le Château is in that sense a full-on ‘relational’ exhibition. Not so much engaging in an interactive game of hide-and-seek with the visitor (that it seems rather to put off than to invite), but rather in relation with an out-side, an environment that is larger than the referential one of the arts.

2. FOOD & HUNGER

Marcella.B& Elke Van Campenhout

1) Food and art production

Knowing about food and where our foods come from, or even knowing what exactly it is we are eating, has been the leveller for a new movement of engaged and interested citizens-artists who want to come to an understanding of the different factors that are running the all-encompassing trade of our alimentary products. Talking about global food production, we must come to the conclusion that making 'healthy' decisions is an almost impossible task. Faced with the everyday realities of food miles, (the lack of) farmer’s organization or union support, the huge gap in economic power between the industrialized mega-states and the (often poor) production regions, the carbon footprint of global distribution, the non-ecological industrialized farming methods and the subsequent constant production of toxins, the limited range of possibilities of the ‘fair trade’ label etc., we come to the conclusion that eating healthily and taking care of your body does not necessarily mean you are taking care of the community or the environment. Taking into account the situation of the workers that are producing your food for less than the money they put into their work, as a direct result of the so-called 'free trade' (but heavily subsidized) food policies promoted by the strong industrial food powers, it is hard to find your way around the shopping isles of your supermarket. But even the neighbourhood shop or farmer’s market is not above suspicion. In the food industry, nothing is what it seems.

In response to this seemingly insurmountable problem, artists and citizens alike have taken up the challenge in very different ways. Collectives concentrating on city gardening, gathering food in public parks, working on solar energy or devising alternative economies are all interesting and locally invested initiatives that somehow try to grasp some of the leftovers of the individual agency in matters that seem largely to surpass its level. Because there are few characteristics that shape our current food production that are not so easily airbrushed by good intentions and local initiative.

The first and probably most important fact is that Food is Class-Conscious: the way food production and distribution is organized today has created, aggrandized and sustained major inequalities in our society: at the city level as well as at the global level, not to forget the discrepancy between the attention dedicated to city (consumers) and the rural community. In the cities American studies have shown that it is hard to find any decent supermarket in predominantly black neighbourhoods. The ‘good’, but also often the cheapest food, is to be found on the outskirts of the city, impossible to reach by foot or public transport. Local, inner-city shops often offer lower quality products at a higher price. Which offers the have-nots only a limited choice: since no fresh produce is available they depend on nightshops, local, relatively expensive small-scale super markets, or just don’t bother and go to the Mc Donald’s, which in these neighbourhoods is always just around the corner. Although this study was performed in the megalopolitan areas of the US, whose structure does not exactly mirror similar-sized cities’ organization in other countries, it is safe to say that equal access to fresh, healthy and nutritious food is limited for those who live on limited means.

This glaring inequality does no more than reflect the same kind of imbalance produced by the global food market system: over-subsidized food industries in nations like the US and China dominate the market by artificially bringing down the prices for the goods produced in other parts of world. Since they are not forced to sell, they can sit back and wait until the market turns out more profit, which is something most other regions cannot afford to do. On top of that, the US has been consciously overproducing (especially corn and grain), and dumping their excess produce on the world market at prices that often are below the cost of production. This is a sure way of cutting down all competition, forcing whole countries into the subservient state of mono-culture produce for mega-companies that are putting even more pressure on the farmers, and rendering them in that way completely dependent on the often capricious swifts and turns of the market and the weather.

What concerned artists-citizens are concentrating on, is to find ways out of this globalized and subsidized inequality system that is fed to us every day when we go shopping, and come to the understanding that there is no locally grown produce to be found, since it seems cheaper to transport apples over 3,000 km to the supermarket than to eat the ones the soon-to-go-out-of-business local farmers are producing. What they reclaim as human beings is their right to food sovereignty: the right to be able to make the right choice. Or as the activist group Via Campesina formulates it in mock response to the WTO demand for the elimination of trade barriers between the nations: ‘Access to markets? Yes, we want access to our own markets’.

Food sovereignty in the first place has to do with accessibility, as said before, and with the communally constructed rethinking of sustainable food architectures in our communities. But there are also more radical ways to put into question the hierarchies and dependencies of the food market, as the hunger artist exemplifies.

2) Hunger as an artistic attitude

Working as a hunger artist means you distance yourself from the world. Food is what greatly shapes our social relations, our daily schedules, our meetings and our professional environments. Try to imagine not being able to go out for dinner anymore, have a beer with a friend until late in the night, go to a business lunch meeting, have a glorious Sunday brunch with the family. What does it produce if you break off all these easy and light engagements that somehow keep your network, your links with the world outside of you, intact? The hunger artist will always be the one who introduces a kind of friction in the social setting, the one who doesn’t play the game anymore, the one who sits soberly watching the others. It is an awkwardness that creates distance, provokes questions, and – more often than not – a certain degree of scepticism or even hostility.

For the hunger artist the body turns into a completely different vessel: slowly hollowing itself out it becomes little by little a pure shell, a testimony of the practice that carries itself outwards into the world, the inner core emptying itself out every day a little bit more. The hunger artist is, to speak in Deleuzian terms, the ultimate Body without Organs (BwO). Deleuze speaks about different types of BwOs: the masochist, the anorexic, the addict, etc. Each of them develops a ‘micro-politics’ that will leave the body undone, stripped of all it organs, of its most essential machinistic sense of functioning. The body seen as a machine that has to be filled up every so many hours is dependent on the food architecture he/she lives in to do so, has formatted his/her social environments to fit into these pigeonholes of meeting and exchanging. In contrast, the BwO opens up the possibility of a body that is no longer mechanical, that frees itself from its dependencies, only to reconstruct them from a new perspective. A BwO is assembled out of a desire for experiment, for the potential breaking through. It pushes the organizational lines of time and space that regulate our ordinary social encounters. “If the machine is not a mechanism, and if the body is not an organism, it is always then that desire assembles.”

The hunger artist, much like the anorexic as Deleuze sees him, reorganizes the social space. When distanced from the initial desire to consume, prompting us into obeisance and consumerism, food items start to tell a completely different story. Walking through the aisles of the supermarket, the long rows of repetitive food items take on an almost alien characteristic. The absurdity of the abundance of food, of this constant movement of goods from the other side of the world, from the rural areas, into the city, keeping the heart of our community pumping takes on an almost grotesque character. Taking a distance from the food object is a first step towards questioning our dependencies. Not only on eating, but on how these food items shape our lives and relations.

The reason the hunger artist is often looked at warily is because he questions our sense of pleasure and the social bonds that create it. Food has, of course, more than a nutritional value: food marks the important moments in our lives, it is an indicator of good taste, of worldliness, and – not unimportantly – of class. Food places us fixedly on the social map of belonging. We buy certain products because our parents did so, because the advertiser sold me his body image, because of the comfort of its proximity, because of our craving to be ‘filled up’. It is no coincidence that ‘comfort food’ as preached on so many TV channels and in countless cook books is often fatty and ‘nostalgic’: referring to a previous age, childhood recipes which remind us of home, of the clear safe boundaries of a house in proper order. Comfort foods are our vessels of consolation, not by coincidence mostly targeted at single consumers. They are the consolation for not fitting the social pattern (yet). Comfort food is what creates food addicts and a dependency on food as a social and/or professional readjuster. No wonder then, that from this perspective the hunger artist is seen as a loco, and the anorexic as diseased. In reaction to the full plate of riches offered to him, he declines politely, as Bartleby did before him: ‘I would prefer not to’ (it is no coincidence that Melville’s Bartleby dies of starvation at the end of the book).

But if we look at the hunger artist from a bit more distance, we could argue that he is probably the true ‘relational aesthetics’ manager. Having become a pure exterior, he rearranges the borders of social conduct. If we go back to the anorexic, we see that the ‘I’ of the anorexic undeniably rearranges the fabric of the family constellation. In the same way, if we see the hunger-artist practice as a public, artistic practice (which it would have to be to overcome the limits of the narcissistic experience), the ‘I’ of the artist is restructuring the relations among the bodies he is closest to: his collaborators, curators, programmers, public, providers, care-takers and so on. By refusing the imposed organized ways of dealing, by making them impossible to apply through a pure passivity of food denial, he rewrites the potential outcome of the situation introducing this simple moment of openness for what might be there on the other side.

As Deleuze notes, the anorexic is not the one that refuses his/her own body, but the one that refuses a particular ideology of the body. It is not the one falling victim to his/her own body, but the one emancipating it from the all-encompassing demands of its environment. It is a twisted logic of the current food system that on the one hand produces more and more fatty and unhealthy food items, and on the other glorifies a perfect, trained, ‘normal’ body, shunning the rest of us out of vision. Out-of-size bodies are the ones that launch a counter-attack against the hypocritical and often obtuse moral hygiene of the food market. Why anorexics as well as overweight people are regarded suspiciously is because they trespass the norm, the middle space, the common ground we all agree on. But if we gave a more militant reading of this ab-normalcy we could say that ‘the anorexic void has nothing to do with a lack, it is on the contrary a way of escaping the organic constraint of lack and hunger at the mechanical mealtime’. The psychiatric reading of anorexic practices or the undue fear of the hunger artist ignore other traditional ways in which these practices were considered spiritually liberating and ascetic practices experimented with for thousands of years. As echoed through the witnessing of these traditions the hunger practice is an emancipatory gesture taking a temporary distance from being subjected to the body’s incessant and dictatorial demands.

During le Château Marcella.B picked up on these intuitions and sent out a call for hunger artists all over the world(in response to the score of Morice Deslisle) to strive for an artistic practice that is built on social transformation, fair trade and the rethinking of the relation between our own and other bodies out there in the world. In a second phase she worked on the development of her ‘Pratiques Anorexiques’ in different, public residency settings. In her practice she points out the parallel between the ways we deal with food and the ways we deal with our arts practices. Using the body as a transformative tool in the exploration of current societal questions of course places the artist right back into a tradition of long-term body arts – but also, and more importantly in this context, in the middle of a societal debate that is larger and more accessible to a larger group of stakeholders than the restriction to the usual suspects of the arts scene. The hunger and anorexic practices open up a field of debate that can be shared by anyone, offer an opportunity to digest various concerns, and incorporate them into the empty body of the artistic work.

Of course the Hunger Artist is only one way to deal with the questions raised by global food production. Overall the strategies that deal with these questions are based on creating a ‘state of attention’ which can be achieved through creating zones of attentive cooking, building sustainable food architectures, inventing new foods, etc. What the Hunger Artist offers in this whole debate is a moment of standstill, a period of tranquillity in the middle of the roaring velocity of movement and speed that directs our existence. A moment of suspension in the eye of the storm.

3) Fair trade in the arts: take out the middlemen

If we talk about fair trade in the food industry we talk about returning to the farmers the right to be paid fairly for what they grow. We talk about the unfairness of the middlemen, the refiners and distributors of the food, the supermarket chains that push the prices up for the customers and down for the growers. We talk about a clear policy on what exactly it means to deal within 'free trade', when the big industrialized nations are paying massive amounts of money to over-produce bulk food which destroys the (potentially) healthy price competition regulating the markets. We talk about over-subsidizing governments that don't take into account the needs of the farmers or of the consumers. But most of all we talk about the right to decide how and what to grow, on the farmer's side, and to be able to make healthy and informed decisions, on the consumer’s side.

If we talk about the arts market, we seem to have entered into that same state of deadlock. Policymakers and commissions, curators and programmers, everyone is trying to make sense of something that should be fairly simple. There are artists producing a multicultural (in opposition to the monocultural agricultural practices) range of practices and artworks, and there is an equally multi-oriented public, looking in the arts for a satisfactory reply to questions or cravings as diverse as critical awareness, aesthetic pleasure, soothing reassurance, political insights, historical framing, and lots more. What has been happening in the last ten years, though, is a subsidizing policy that grew out of a more or less sane self-organizing artists’ field, and that now has become regulative to an almost absurd degree. (We write here from our background as a respectively Dutch and Belgian artistic researcher.)

In his State of the Union address at the performance festival in Belgium, a few days after the Dutch cultural subsidy system all but collapsed under the weight of populist demands and managerial efficiency, cultural sociologist Pascal Gielen rightly remarked:

“The arts field follows a ‘neutral politics’ strategy. One doesn’t utter politically tinged statements, one speaks with just about all democratic parties, one provides evenly divided political distribution in the boards and even sometimes in the governmental commissions. At the same time one incorporates the efficiency and management rhetoric that pleases today’s policymakers: the arts sector as well wants to prove its ‘good management’, while research ought to legitimate the arts sector economically”. As a direct result of this managerial approach though, Gielen claims, the arts sector opened up the possibility for its most interesting, experimental, ‘non-efficient’ practices to be cut from one day to the other. Because this kind of understanding of ‘good policy’ “has a politically coloured history, stemming from the UK politics of Margaret Thatcher, and is certainly not politically neutral since it joins forces with the neo-liberal rhetoric of the free market as the fundament of our society. And does that with all semblance of political neutrality”. As pointed out above, the cultural scene in the Netherlands was crushed by its own embrace of neo-liberal newspeak. In Belgium, the sector is crushed by the slowly suffocating motherly hug of the subsidiary system. Mom says what we should wear, where we have go to school, how we should behave and present ourselves in public. Mom tells us which words to use in our files, and who to address to 'step up' the social and professional ladder. The problem is that in this sector, too, the cards are being dealt by the middlemen, by the producers, and subsidizers. Although of course most of the programmers and curators also are stressed into defending their 'niche format', their 'name' and their 'brand'. Just as the many commission members and cabinet members and other advisers and decision makers probably have the sector's best interest in mind. The problem is not with the individuals, trying to grasp the reality of what is happening, and responding accordingly. The problem is that the system little by little has made itself indispensable, has become the (half) hidden ruler of the arts. A system that has produced format after format for production, creation, research, distribution and sales is now desperately trying to fill in the holes of the raster, but cannot see over its little dividing walls what is happening outside. What people are processing outside of these well-prepared holes in the wall. Which is no wonder, since nobody will ever be able to see what these artists are doing since they didn't fit the profile of the venues they were supposed to be shown in, or meet the people that might have appreciated what they do. If we talk about fair trade in the arts, then, I think we talk about a fair chance, not only for artists, but also for experimental programmers and curators that don't tick all the ‘salonfähigkeit’ boxes of what is hot today. We talk about the public as well, that is often confronted with a made-to-custom programme that is supposed to serve all tastes. And we are evidently also talking about policymakers that should not be burdened with the power to decide who has and who has not. If we talk about fair trade we're talking about giving the power (and the money) back to the artists: let them decide what to do with all these heaps of bricks supposedly built to host the artist's and the public's interest. Let them meet with these publics directly, uncensored, and let them find out what it means to take position. What it means if art again starts to mean that you stand for something, and that we can disagree. Violently or not. And that we can do this directly. Where free trade meets fair trade. What would the sector look like then?